Nothing Happened All at Once: Becoming Used to Things

Books, Curiosity, and the Long Arc Toward Cuba

Growing up, my parents kept a lot of books in the house. We were a family that had annual editions of encyclopedias from World Book and Britannica. There was exposure to many different types of books and ideas. By the time I was a young teenager, I had read through both the Bible and the Qur’an at least once. My thirst for books and reading was insatiable.

As I moved down the bookshelf, I came across a book in my younger years titled Soledad Brother by George Jackson. Reading George Jackson’s accounts piqued my interest. By the time I was graduating high school, I had been exposed to the works of people like Angela Davis, Kwame Ture, and Malcolm X. Inevitably, I encountered the work of Assata Shakur. I was inspired by her and deeply curious about the place she had retreated to.

I knew of Cuba largely through Cold War narratives about the Soviet Union. But reading Assata Shakur’s autobiography made me even more curious, and I began to dig. I learned that Angela Davis had also spent time in Cuba. Then I learned about the U.S. trade embargo. I wondered how it was that a place where Black revolutionaries from the United States found refuge was simultaneously a place that the United States actively shunned. That contradiction unsettled me, so I kept digging.

By my early twenties, was exposed to The Motorcycle Diaries, which introduced me to Che Guevara. I was fascinated by what I perceived as his quiet revolution. I made comparisons between Che Guevara and my own favorite American revolutionaries: Fred Hampton, Huey Newton, Eldridge Cleaver, and artists who staged revolution through music and writing. I could not get enough.

Learning about the Cuban Revolution led me to research and, at times, romanticize the ideas of the Castro brothers and Che Guevara. For decades, I longed to visit Cuba and see for myself what it was about this nation that had provided a safe space for U.S. revolutionaries. Travel was restricted at the time, but my fascination with and imagination of Cuba as a revolutionary place never faded.

Finally Arriving

In 2023, my partner asked where I wanted to go for my birthday. There were a few places I had wanted to visit for as long as I could remember, especially places that had once been inaccessible. I told him to see how much it would cost to go to Cuba. The flights were cheaper than traveling to the west coast of Africa, so we booked the trip.

We landed in a small airport. The sun was bright. The weather was perfect, neither too hot nor too cold. The people were beautiful. We rested for a while and then wandered out. We had somewhat of a concierge who met us at the airport, provided lodging, assisted with currency exchange, and gave recommendations for food, and suggestions for places we should, and should not wander into.

I was especially excited because on our second day I had scheduled a tour with a sociologist from one of the universities. He was brilliant. We walked through Old Havana and New Havana as he narrated the history of the country. We visited the ocean and historical landmarks. We discussed religion and other vital components of culture. It was powerful to place my eyes on locations I had only ever encountered in books and in my imagination.

By this time, I had taught sociology for nearly two decades, and Cuba is one of the countries I highlight when teaching Race and Ethnic Relations. Much of what the tour guide shared, I knew in a theoretical sense. But hearing him describe his lived experience through a sociological lens was something else entirely.

A Policy, a Reaction, and a Shift in Perspective

At one point on the tour, our guide began discussing a particular U.S. policy directed at Cuban migrants. As soon as he named it, I recoiled and said, “That’s a terrible policy.” He stopped walking and asked why. We stood for some time, exploring our perspectives on the policy – perspectives divided by an ocean.

I explained that the policy was racist. If a Cuban citizen attempted to leave Cuba and was intercepted at sea, they were returned. But if they made it to dry land, they were allowed to stay. This policy did not exist for most other groups beyond Cubans and Haitians. It was not rooted in benevolence; it was rooted in racialized geopolitics.

Our tour guide nodded patiently. Then he paused and said something that stopped me. He explained that even the chance of making it to dry land created hope. For those who succeeded, the policy allowed them to pursue permanent residency and eventual citizenship, enabling them to send remittances back to family members who desperately needed the money.

That conversation was an eye-opener. Policies are never just one thing. I had entered Cuba expecting to confirm a set of beliefs. Instead, I was forced to widen my view and adopt a stance of “I don’t yet know what I will find.”

As we toured and chatted, I was struck by the communal feel of the city. By the way people laughed together and created art together. By the way neighbors held each other’s places in long lines as they waited for their small monthly rations. I was moved by the third spaces people created to sit, share, argue, and laugh. There was joy.

People adapt to maintain their humanity.

People also adapt at the expense of their humanity.

Both can be true at the same time.

Adaptation and evolution are necessary for survival.

Seeing the Reality

Sometimes when we open your eyes to the reality, we really see. What I found was an extraordinary level of poverty and oppression. A lack of food, medical supplies, and basic necessities plagued the country. Restaurants changed their menus daily based on food items that they had access to, often only having one or two items available. Buildings crumbled, and the ruins left unrepaired and unlivable, yet lived in by a people with no options. As the tour continued, the guide offered snapshots of everyday life. It became apparent that Cuba was not, and had likely never been, the threat it was painted to be. In fact, the history of enslavement, colonization, hopes for statehood, and resistance shaped the story far more than political ideology. In fact, the violent actions of our own country against the Cuban government made life for the average Cuban citizen more desperate. It also became apparent that on one side, the so-called saviors were also oppressors. The strong man who saves often becomes the strong man who oppresses.

I returned home and kept digging. I read more history, watched documentaries, and listened to firsthand accounts of Cuban people. One thing stood out clearly: culture does not change overnight. Culture changes gradually. And as it changes, people adapt.

Holding Cuba with Care

I want to pause here and be clear about something. While my experience in Cuba was an extraordinary learning experience that forced me to confront my own romanticized assumptions, the country of Cuba and the Cuban people are not deficient. The conditions I witnessed are not the result of inadequacy, laziness, or moral failure. They are the result of a long and complex historical and political story shaped by colonialism, foreign intervention, economic isolation, and fear.

Cuba is beautiful. The people are beautiful. And the story of Cuba can be held as a cautionary tale not because of who its people are, but because of how cultures and societies adapt to harm and how that harm reshapes daily life. It is a story about impact, not blame.

The beauty of humanity is that we adapt. The sadness of humanity is that we adapt.

Centrist politics is a facade

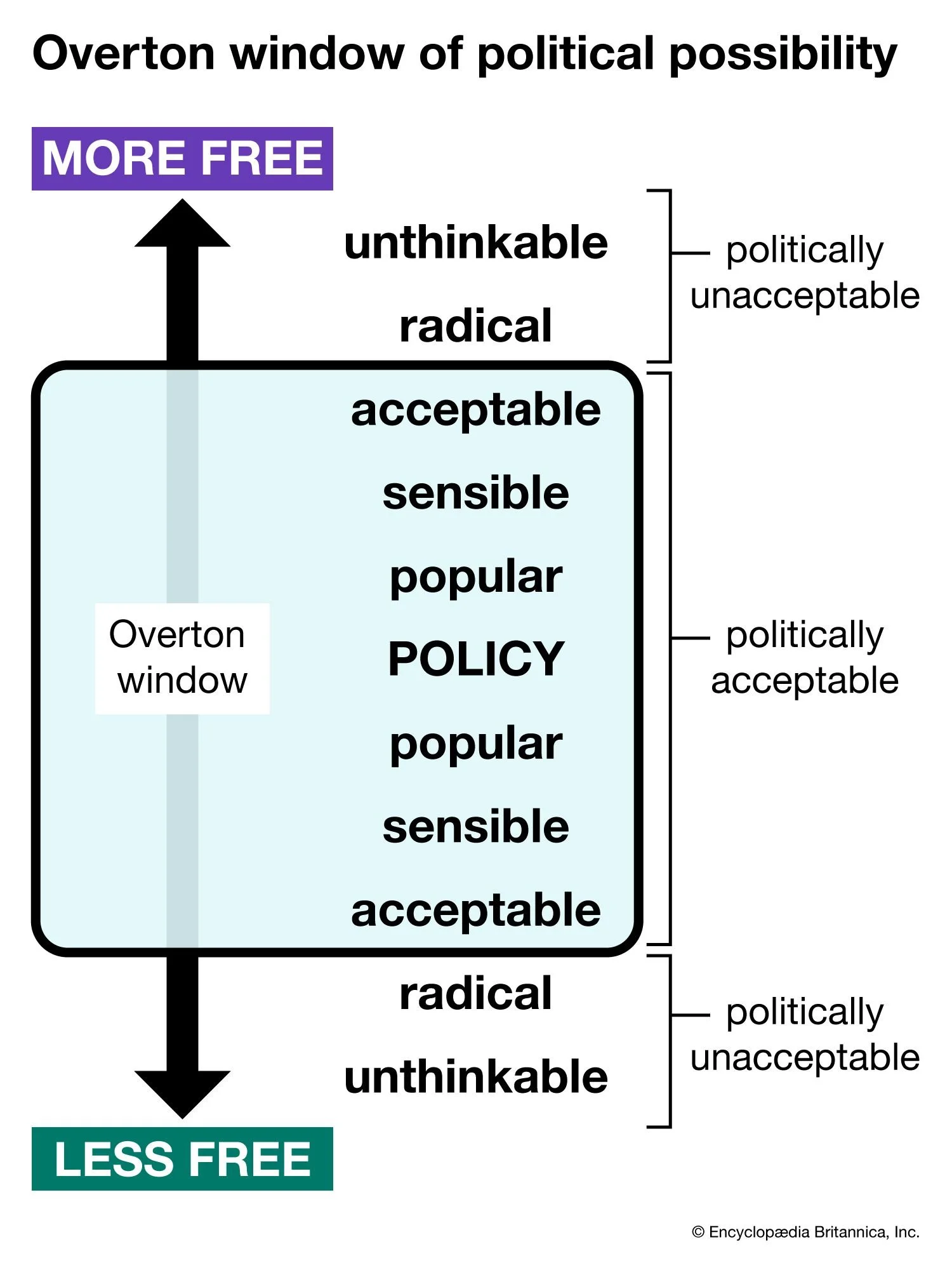

What I could not stop thinking about, long after I returned, was not whether Cuba was “good” or “bad,” but how quietly a culture can learn to live inside constraints without ever being asked if it agrees to them. How harm does not always arrive as violence, but as gradual accommodation. How people do not consent to loss so much as adjust to it. I kept thinking about how freedom rarely disappears all at once. It narrows. Slowly. What was once unthinkable becomes radical. What was once radical becomes debatable. What was once debatable becomes sensible. And eventually, it becomes policy. This is how cultures adapt without consent. This is how the room tilts while the mirror fogs. And this is why conversations about “centrist politics” are so hollow without asking: centrist based on when? Based on which baseline of freedom? Because centrism is not neutral. It is relative to what is already acceptable. And when the window has already shifted, standing in the middle does not mean balance. It means accommodation. The beauty of humanity is that we adapt. The sadness of humanity is that we adapt. People adapt to preserve joy, to preserve connection, to preserve dignity. And sometimes, people adapt at the expense of imagining anything different. The most dangerous moment is not when harm is obvious, but when it becomes ordinary. When constraint feels less like theft and more like weather. Something we plan around. Something we endure. Something we stop questioning. I left Cuba not afraid of becoming like another country, but unsettled by how easily any society can become comfortable inside a shrinking room.

Adaptation, Normalcy, and the Overton Window

As I reflect on the ideas of adaptation, evolution, and culture, I want to also consider the Overton window.

The Overton window is a political and sociological framework that describes the range of ideas, behaviors, and policies that are considered acceptable or “normal” within a society at a given time. Ideas outside the window are considered unthinkable or extreme. Ideas inside the window feel reasonable, practical, or inevitable.

The window is not fixed. It shifts slowly over time. As it shifts, people adapt to new norms, often without noticing the movement itself. What once felt intolerable begins to feel acceptable. What once felt unacceptable begins to feel normal.

Assata Shakur captures this perfectly:

“People get used to anything. The less you think about your oppression, the more your tolerance for it grows. After a while, people just think oppression is the normal state of things. But to become free, you have to be acutely aware of being a slave.”

Humans are adaptive. We adapt socially, politically, and environmentally. This adaptability is evolutionary and protective. It keeps us alive. But it also reshapes our definition of normal.

Consider how quickly many of us adapted to hybrid or work-from-home models during COVID, and how difficult it was for organizations to force a return to pre-pandemic norms. We adapted because our survival depended on it.

One of the most effective ways to encourage adaptation is to convince people that their lives and livelihoods depend on it. Then, convince members of the group that their survival also depends on each other’s compliance. This creates not only adaptation but also self-policing. Normalcy becomes enforced, protected, and defended, even by people who once challenged it.

“This is just how it is” becomes a survival strategy, offering protection and simultaneously draining hope. It also drains hope.

Those in power understand that hope fuels imagination, and imagination fuels resistance. When hope is stripped away, creativity disappears. Without imagination, people cannot envision a different reality. And so they adapt.

In 1897, Sociologist Emile Durkheim used the concept of anomie to describe a condition of normlessness, a breakdown in the shared moral and social frameworks that help people make sense of their lives. Anomie is not chaos in the loud sense. It is disorientation. It is what happens when the rules no longer feel clear, fair, or tethered to a shared social good.

When anomie takes hold, people lose a reliable sense of what effort leads to what outcome. Expectations dissolve. Promises feel hollow. Over time, this erosion produces hopelessness: the belief that nothing will meaningfully change regardless of action. Hopelessness then calcifies into helplessness, a learned conclusion that one’s behavior has no impact on the larger system. And helplessness, left unattended, becomes inertia. Not resistance. Not rebellion. Stillness.

This is not apathy. It is exhaustion shaped by structural uncertainty.

In an anomic context, people are not choosing disengagement so much as they are adapting to a world that no longer offers a coherent moral map. Movement feels risky. Effort feels wasteful. Staying put feels safer than acting in a system that no longer rewards meaning, dignity, or reciprocity.

And thus, anomie quietly impacts the movement of the Overton Window.

As shared norms erode, the range of what feels politically, culturally, or morally possible shrinks. Not because people suddenly agree with the harmful conditions, but because anomie lowers collective expectations. When people no longer believe that better is achievable, the window narrows around survival rather than justice. Around stability rather than transformation. Around what can be endured rather than what should be changed.

In this way, anomie does not just reflect social breakdown; it actively stabilizes harmful systems. Hopelessness dampens imagination. Helplessness weakens agency. Inertia preserves the status quo. And the Overton Window shifts not through persuasion, but through resignation.

What becomes “reasonable” in an anomic society is not what is right, but what people no longer believe they have the power to refuse.

Fear as a Cultural Driver

Sadly, one of the primary drivers of anomie in American culture is fear.

Fear of the other. Fear of scarcity. Fear of loss of status. Fear of discomfort. Fear of change. Fear of telling the truth. Fear of what happens if we stop pretending that things are fine.

Fear is a powerful organizing force. It shapes policy. It shapes media narratives. It shapes who is framed as dangerous and who is framed as deserving. It shapes which lives are protected and which lives are treated as expendable. And most importantly, fear shifts the Overton window.

When fear takes hold, the range of ideas considered “reasonable” does not disappear. It relocates. Policies and practices that would have once been considered extreme, unethical, or unthinkable are reframed as necessary, pragmatic, or inevitable. At the same time, ideas rooted in care, justice, or collective responsibility are pushed outside the window and labeled naïve, dangerous, or unrealistic.

Fear accelerates adaptation. When people are afraid, they are more willing to accept surveillance, restriction, and control if those measures are framed as protection. They are more willing to surrender autonomy in exchange for the promise of safety. Over time, this trade begins to feel rational rather than coerced.

Fear also constrains curiosity. Curiosity requires uncertainty and openness. Fear demands certainty and control. It pulls people toward simplified narratives, rigid boundaries, and strong figures who promise order. In this way, fear is not just an emotional response; it becomes a cultural strategy.

Make it stand out

Overton Window

As fear becomes normalized, people reorganize their lives around it. They begin to police themselves and each other in its name. The shifted Overton window no longer feels like a shift at all. It feels like common sense. And so people come to say, softly and then aloud, “This is just the way it is.”

Fear and the Threat of Violence

One of the conversations we kept returning to while in Cuba was the constant, ambient threat of violence. Not always visible. Not always enacted. But present. Felt. Understood.

When cultures are forced into drastic change, that change often begins with state-sanctioned physical violence. Bodies are used to teach lessons. Fear is introduced as a language. The message is made unmistakably clear: this is what happens when you resist.

Over time, once the ideology has been installed and the norms have settled into place, physical violence becomes less necessary. Not because power has softened, but because it has become efficient. The threat remains. And the threat alone does the work.

This is reinforced by normalcy bias—the human tendency to interpret prolonged threat as stability—so what is dangerous slowly comes to feel ordinary, and what once felt intolerable becomes simply “how things are.”

Normalcy bias refers to the cognitive tendency to underestimate both the likelihood and impact of ongoing or escalating harm, leading individuals and groups to interpret abnormal or dangerous conditions as stable, acceptable, or inevitable over time.

In everyday terms, normalcy bias is what happens when people slowly get used to what should never have been okay. When harm does not arrive all at once, but instead lingers, repeats, or becomes part of the background, our minds and bodies adjust in order to survive. What once felt alarming starts to feel familiar. What once demanded action starts to feel unavoidable. Over time, people stop asking whether something is right or wrong and begin asking only how to live within it.

That constant threat of violence is itself a form of psychological, emotional, and relational violence. It teaches people how to move, how to speak, what to say out loud, and what to never name. It teaches the body before it ever teaches the mind. It keeps people in check not through force, but through anticipation.

And thus, this is how culture changes without appearing to change at all, shifting the Overton Window.

What was once unthinkable becomes thinkable. What was once unacceptable becomes tolerable. What was once intolerable becomes normal. Not because people consented, but because people adapted. The range of what can be safely imagined, spoken, or challenged narrows, slowly and quietly, under the weight of threat.

Eventually, the absence of overt violence is mistaken for freedom. Compliance is mistaken for peace. Survival is mistaken for agreement.

And the most insidious part is this: people do not experience this as coercion. They experience it as realism. As pragmatism. As “just the way things are.” The window does not slam shut. It drifts. And with it, people recalibrate their expectations of dignity, safety, and possibility.

Culture does not only change through laws or policy or force. It changes through what people learn is too dangerous to want.

A Brief Historical Parallel: Fear and the Shifting Window

History offers countless examples of how fear shifts the Overton window rather than breaks it. One of the clearest examples in the United States is the period following September 11, 2001. In the immediate aftermath, fear became the dominant cultural force. That fear did not eliminate debate or dissent, but it relocated the boundaries of what was considered reasonable.

Policies that had once been unthinkable such as mass surveillance, indefinite detention, expanded policing powers, and the erosion of civil liberties were reframed as necessary for national security. At the same time, questions about constitutional rights, state power, and the long-term consequences of these policies were pushed outside the window and labeled unpatriotic or dangerous.

Most people did not wake up one morning willing to accept a surveillance state. They adapted. The fear was real, the threat was framed as constant, and the promise of safety made the shift feel rational. Over time, what began as emergency measures became normalized practices. The Overton window had moved, and life reorganized itself around that movement.

This is not a story about moral failure. It is a story about human adaptation under fear.

Reader Reflection: Noticing the Shift

Take a moment to pause and reflect.

Think about an issue you care deeply about today. It might be related to race, education, policing, immigration, healthcare, gender, or democracy itself.

Now ask yourself:

· What ideas or conversations felt possible five years ago that now feel risky, exhausting, or “not worth it”?

· What policies or practices would have felt extreme or unacceptable in the past but now feel normal, inevitable, or pragmatic?

· Where do you notice yourself saying, “That’s just how it is,” even when something in your body feels unsettled?

Next, consider fear:

· What fears are being named explicitly in this moment?

· What fears are being implied but not spoken?

· Who benefits from those fears becoming normalized?

Finally, return to your body:

· Where do you feel tension, constriction, or numbness when these topics arise?

· What parts of you have adapted in order to cope?

The goal of this reflection is not judgment. It is awareness. Because the first step in resisting harmful adaptation is noticing that the window has moved at all.

The Meniscus and the Moving Window

A few years ago, I tore my meniscus. The pain in my left knee was intense. Sitting, walking, standing all hurt. I limped for months, aware of the pain but telling myself I didn’t have time to get it checked.

Eventually, the pain felt normal. I adjusted how I stood. I changed the depth of my squats. I forgot how painful a torn meniscus truly was.

Then I was interviewed on the local news. One segment showed me walking down a hallway. Watching myself, I noticed a very visible limp. My gait had changed. It felt normal, but it was profoundly altered.

My window of tolerance had shifted. The pain that was once intolerable had become unnoticed. My body stopped sending clear pain signals. Limping had become normal.

This is how the Overton window works in bodies, cultures, and nations.

From Anti-Racism to “Divisiveness”

In 2020, following police violence and the early days of COVID-19, individuals, companies, and institutions clamored for conversations about racism. Positions were created to ensure that conversations about equity and antiracism were held. Dollars were set aside for programming and other efforts. In 2020, people were hopeful and optimistic about change. So hopeful and optimistic that people went to the polls to vote in very populist ways. As a result, the election of Joe Biden felt like hope realized for many.

And so they stopped.

By 2024, those same conversations that were clamored for in 2020 were being labeled “divisive” or “political.” By 2025, groups moved away from language of progress, as that language was now see as intolerable. Policies and practices that were once praised as progressive were quietly abandoned. What once elicited engagement now elicits defensiveness. Conversations about race began to be seen as political as the Overton Winder shifted and marginalized people became even more marginalized.

Cuba, Fascism, and Gradual Descent

When I traveled to Cuba in 2024, I was not just visiting a country. I was witnessing adaptation in real time.

Cuba’s descent did not happen overnight. The fall of the Soviet Union removed economic support. U.S. trade embargoes compounded scarcity. Fear, isolation, and survival reshaped political life. What emerged was not the revolution I had imagined, but an evolution toward authoritarian control driven by desperation.

The people are without food, money, infrastructure, and access. Buildings collapse around them. And yet, people are smiling. Waiting in line for bread. Walking past hotels they do not dare enter. Shopping in stores priced in currencies they literally cannot obtain; currency reserved for the very small numbers of Cuban elite and European and Canadian tourists.

I wondered how quickly people adapt. How quickly bread becomes a luxury. How quickly hunger becomes background noise. How quickly fascism becomes “just the way it is.”

I wondered if they could still feel the torn meniscus or if the pain had faded into normalcy.

Choosing How We Evolve

Evolution is powerful. It is inevitable. But we are not powerless within it.

We can evolve toward silence, fear, and fascism. Or we can evolve toward resistance, justice, accountability, and truth-telling, even when it is uncomfortable.

As a sociologist, a historian, and someone with a penchant for seeing patterns, I am concerned. What we are experiencing is not new. The pain is acute now. We feel it sharply. Many of us are limping. Some are panicking. Some are disengaging. Some are losing hope.

The danger is forgetting how much the pain hurts.

Evolution will continue. The question is not whether we will adapt. The question is what we will adapt into.

How Quickly Do Countries Move Into Totalitarianism and Fascism?

Countries rarely move into fascism all at once. They move there incrementally, through adaptation rather than announcement. Fascism does not typically arrive declaring itself as such. It arrives framed as protection, efficiency, stability, and necessity, particularly during moments of fear, scarcity, and exhaustion. What enables this shift is the movement of the Overton window. As fear becomes a dominant organizing force, the range of ideas considered reasonable relocates. Policies that once lived outside the window are reframed as pragmatic responses to crisis, while ideas rooted in rights, care, and collective responsibility are pushed beyond the window and dismissed as unrealistic or dangerous. Each adjustment feels tolerable in isolation. Taken together, they transform the political and cultural landscape.

This movement is accelerated by human adaptation. People recalibrate their expectations in order to survive. They adjust to restrictions, surveillance, and control not because they agree with them, but because resistance feels costly or futile. Over time, the shifted Overton window becomes invisible. What was once experienced as a rupture is absorbed into normalcy. The question quietly changes from “Should this exist?” to “How do I live within it?” This is how fascism takes hold not only through force, but through normalization. People learn to limp and forget what it felt like to walk freely.

Cuba offers a sobering illustration. Authoritarian control did not appear overnight. It evolved through economic isolation, foreign pressure, and internal fear. As resources dwindled and options narrowed, the Overton window shifted. Survival replaced possibility. Adaptation replaced resistance. The people adjusted not because the conditions were just, but because adjustment was required to endure. What began as crisis became routine. What became routine stopped being questioned.

A U.S. Parallel: Normalization Through Fear

The United States offers its own parallel. In recent decades, fear has steadily shifted the Overton window around policing, surveillance, immigration, and protest. Practices that once would have sparked widespread alarm such as expanded surveillance, militarized policing, book bans, restrictions on protest, and the framing of dissent as threat are increasingly treated as reasonable responses to instability. Each shift has been justified as temporary, necessary, or protective. And yet, as with all shifts in the Overton window, what begins as an exception becomes an expectation. The danger is not that people suddenly embrace authoritarianism, but that they adapt to it. Fear makes the shift feel sensible. Normalcy bias does the rest.

Choosing Agency Within Adaptation

Cuba taught me that adaptation is not the same as consent. People adapt to survive, not because conditions are just or acceptable. Fear shifts what feels possible, and over time, the shifted window begins to feel like reality itself. But adaptation does not erase agency. It only obscures it. Hope is not naïve optimism; it is the refusal to forget that pain is not normal, even when it has become familiar. Agency begins with remembering that the limp is not the body’s original design. When we name fear, notice the shift, and stay connected to one another, we interrupt the quiet slide into “this is just how it is.” We may not be able to stop evolution, but we can choose what we evolve toward. And choosing justice, accountability, and collective care is itself an act of resistance.

November 2024.

In November 2024, I began writing this piece. It has lived quietly in my notes application on my smart phone ever since, a document I have returned to often. One of the primary motivators for writing was a growing curiosity about the relationship and perceived similarities between the United States and Cuba. Having experienced Cuba as a totalitarian state in 2023, I found myself wondering just how quickly such a shift could occur in the United States.

By late 2024, I did what many of us do when trying to make sense of an uneasy feeling. I Googled “similarities between the U.S. and Cuba.” The results were quick and confident. Google assured me there were none. Cuba, as a totalitarian state, was described as economically, politically, and culturally distinct in ways that made such a comparison not only inaccurate, but impossible. It could never happen here.

And yet, something in me would not settle. Based on what I witnessed during the 2024 election, the pattern felt eerily familiar. Not identical, but familiar. Familiar in the way adaptation unfolds. Familiar in the way fear organizes behavior. Familiar in the way the Overton window shifts quietly rather than dramatically. And I kept returning to this piece. Wondering.

What unsettles me most is not that history repeats itself exactly, but that it echoes. And those echoes are often recognizable long before they are named, especially when normalcy bias convinces us that what is familiar must also be safe, and that gradual change cannot possibly lead to rupture.

I return to this writing now not in disbelief, but with a mix of affirmation and dismay. Affirmation that the questions I asked then were not unfounded. Dismay at how quickly what once felt unthinkable began to feel discussable, then defensible, then normalized. What unsettles me most is not that history repeats itself exactly, but that it echoes. And those echoes are often recognizable long before they are named.

Returning to the Question

I began this writing with curiosity. I return to it with clarity.

What I learned in Cuba, and what I have been relearning at home, is that the most dangerous shifts rarely announce themselves. They arrive through adaptation, through fear, through the quiet recalibration of what feels normal. The Overton window moves not because people stop caring, but because caring becomes costly. Normalcy bias steps in to soften the alarm, to tell us that if something were truly dangerous, we would surely feel it more sharply.

But bodies adapt. Cultures adapt. Nations adapt. And adaptation can look like peace when it is actually resignation.

I do not return to this writing because I am surprised. I return because remembering matters. Remembering what once felt unacceptable. Remembering what pain feels like before it fades into background noise. Remembering that curiosity is not naïveté, and discomfort is not danger.

Evolution will continue. That much is inevitable. What remains within our control is whether we notice the shift, whether we name it, and whether we choose to evolve toward justice rather than convenience, toward accountability rather than fear, and toward one another rather than silence.

Embodied Reflection: Where Am I Adapting Without Consent?

Find a position that allows your body to settle. You do not need to close your eyes unless that feels supportive. Begin by noticing your breath without trying to change it. Notice where it moves easily and where it feels constrained.

Now bring gentle attention to your body. Scan from your feet upward. Where do you feel tension, numbness, or quiet fatigue? Where does your body feel braced, guarded, or prepared for impact? Do not try to fix anything. Just notice.

Consider this question slowly: Where in my life have I adjusted in order to survive, not because the conditions are just or acceptable, but because adaptation felt necessary?

As you hold that question, notice what your body does. Does your jaw tighten? Does your breath shorten? Do your shoulders lift? Do you feel a familiar heaviness, or a dulling of sensation? These are not failures. They are signals.

Now ask: What once felt unacceptable that now feels normal?

Where have you changed your gait, your depth, your posture, your voice? Where are you limping in ways that feel invisible to you but might be visible to others?

Finally, place a hand wherever your body seems to ask for contact. Let that touch be a reminder rather than a demand. You do not need to act, decide, or resolve anything right now. Awareness is the work.

End with this quiet truth: Adaptation kept me alive. Awareness gives me choice.

When you are ready, return your attention outward, carrying with you the knowledge that noticing the limp is not weakness. It is the beginning of agency.

CUBA

Forever memories.

Signing a wall of remembrance.